|

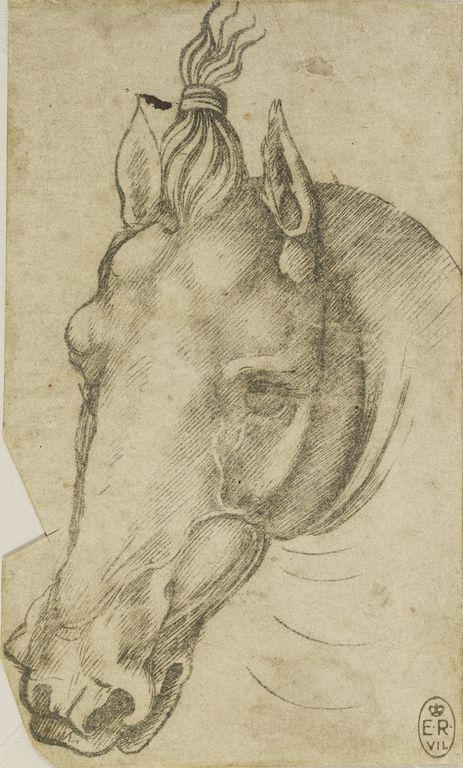

| Horseman of Montecavallo Yale Center for British Art George Romney, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Timeless Art of Drawing Horses: From Symbol to Sketch

Introduction: The Horse in Human Imagination

There are ancient and enduring reasons why the horse has galloped through our histories, legends, and imaginations with such power. The horse is more than a creature of strength and grace; it is a symbol of movement, of freedom, and of deep companionship.

Since time immemorial, horses have carried humanity across plains, through battles, over mountain passes, and into the very heart of civilization.

In times of peace, the horse tilled our fields and bore our children. In times of war, it thundered beneath us as an emblem of courage. The horse is not merely an animal — it is a bridge between humankind and nature, between survival and artistry.

To draw a horse is to engage with this profound legacy. Every sketch becomes more than an exercise in line and shade; it becomes an act of communion with history itself. Horse drawing is at once technical and poetic, requiring a careful balance of anatomy, proportion, and spirit. With the sharpened graphite of a pencil, the horse becomes a noble muse — its sinews, its spirit, its subtle gaze captured on paper.

The Line Between Reality and Imagination

One of the most fascinating aspects of drawing horses is the tension between what we see and what we imagine. An artist may begin with a live horse, a photograph, or even a memory. Yet the finished artwork is never a replica; it is a translation. The act of sketching transforms a three-dimensional living being into two-dimensional poetry.

This is where the artist’s role as a translator emerges. A horse sketch is not simply about replicating muscle, mane, or bone structure. It is about capturing the essence — the freedom of a gallop, the intensity of an eye, the softness of a resting head. Art allows us to bypass the literal and embrace the imaginative. Whether guided by a reference photo or a fleeting memory, the artist’s vision breathes life into the page.

|

| Image generated with the assistance of ChatGPT (OpenAI). |

From Sketch to Masterpiece: A Historic Practice

Throughout history, horse drawings have served as the foundation of artistic practice. In the Renaissance, drawing was not considered the “final art form” but rather the skeleton upon which painting, sculpture, and architecture were built. Masters such as Leonardo da Vinci sketched countless horses in pencil and chalk before committing them to larger works.

Cathedrals, palaces, and equestrian statues all began as tentative lines on parchment. A pencil sketch was not a mere warm-up but a thinking process — a way for the artist to become familiar with the curves of a horse’s neck, the tilt of its ears, or the angle of its stance. Even today, seasoned artists use quick sketches to test proportions, explore poses, and experiment with shading before working on a final piece.

Thus, to sketch a horse is to engage with a tradition that spans centuries, linking modern pencil drawings with the roots of European, Asian, and Middle Eastern art.

The Poetry of Shade and Line

Drawing a horse is never just mechanical. Every line carries rhythm, every shadow carries weight. Pencil drawing, chalk sketches, and crayon art are part of the artist’s primary toolkit — but what elevates them is the poetry of shade and line.

A fine line can suggest delicacy: the gentle curve of a nostril or the whisper of a mane. A heavy, dark stroke can convey power: the tension of a galloping leg or the muscular stretch of a back. Shading, too, becomes expressive. Through careful gradations, an artist can suggest depth, volume, and atmosphere.

To shade a horse is to sculpt with graphite. The pencil transforms into an instrument of light, enabling the artist to capture everything from the gleam of a horse’s eye to the soft shadow beneath its belly.

The Horse as Muse

Why does the horse remain such a compelling subject for artists? Part of the answer lies in its dual nature: it is at once practical and mythical, both servant and symbol. The horse represents strength, movement, and loyalty — qualities that resonate deeply with human experience.

Artists are drawn to the horse because it embodies grace in motion. To capture a gallop on paper is to freeze freedom itself. To sketch a resting mare is to preserve serenity. Whether depicted in dynamic poses or quiet stillness, horses offer endless inspiration for both beginners and masters of drawing.

For centuries, horses have appeared in cave paintings, medieval manuscripts, Renaissance sketches, and modern illustration. Each drawing is not just an image but an homage to a creature that has shaped civilizations and imaginations alike.

|

| Image generated with the assistance of ChatGPT (OpenAI). |

The Technique of Shading a Horse

For anyone learning how to draw horses, technique matters as much as inspiration. The tools of horse drawing are humble yet powerful:

-

Paper: A pristine sheet of white drawing paper, ideally 120 gsm or higher, provides optimal texture for pencil strokes.

-

Pencils: A reliable set of graphite pencils ranging from hard (H2, H4) to soft (B6, B8) allows the artist to achieve both fine precision and deep shadows.

-

Reference Materials: A high-resolution black-and-white photograph of a horse can help capture anatomy and lighting, though a vivid imagination remains the artist’s greatest resource.

The process often begins with light, exploratory lines to establish proportions. Once the structure feels balanced, the artist gradually builds layers of shading. Harder pencils define outlines and subtle tones, while softer pencils add depth, shadow, and contrast. The blending of these strokes creates the illusion of volume — the curve of a ribcage, the shine of a mane, or the tension of a tendon.

From Paper to Painting

While pencil sketches can stand on their own as finished artworks, they often serve as the foundation for paintings. Historically, many equestrian paintings — whether portraits of kings or depictions of battles — began as simple graphite outlines. The drawing stage allowed the artist to solve compositional problems before introducing color.

Even today, digital illustrators and painters rely on preliminary sketches when creating equestrian art. A horse sketch establishes movement, anatomy, and flow, enabling the artist to later experiment with watercolor, oil, or digital layers.

Thus, the pencil is not only a tool of immediacy but also of preparation. Every painted masterpiece owes its life to the quiet work of pencil lines.

A Last Word on the Pencil

To ask, “What is a pencil?” is to ask what it means to begin. The modern pencil emerged in the 15th century and became popular in the 17th century when rich graphite deposits were discovered. Suddenly, artists had access to a wide range of tones and textures.

From the delicate control of an H2 to the dark richness of a B8, the pencil offered infinite possibilities. What began as a simple writing instrument evolved into one of the most versatile artistic tools in history. For horse drawing in particular, the pencil remains unmatched. It allows precision for delicate details — like eyelashes or hooves — and freedom for bold, sweeping lines that suggest movement.

The pencil is quiet yet powerful, ordinary yet extraordinary. It is the gateway through which imagination meets paper.

Conclusion: The Horse as Artistic Legacy

To draw a horse is to step into a timeless dialogue between humankind and nature, between memory and imagination. Horses have carried us physically through history, but they also carry us artistically into realms of freedom, courage, and beauty.

The act of sketching a horse is never just about anatomy. It is about capturing essence. Every line is a gesture of respect; every shadow is a reminder of movement. Whether as a quick sketch in the corner of a notebook or a full-scale graphite masterpiece, horse drawings connect us with an ancient tradition of creativity.

Ultimately, the horse remains more than a muse. It is a symbol of freedom, a companion in both life and art, and a subject that continues to inspire artists across the world. With nothing more than a pencil, a piece of paper, and a vision, anyone can bring the horse to life — galloping once more through the fields of imagination.

The Remarkable Power of Pencil Shading in Art

The humble pencil, often viewed as a simple tool for sketching, possesses a remarkable and often overlooked power. Its true magic lies not in its ability to create a line, but in its masterful control of shadow. It is through sensitive pencil shading techniques that an artist can move beyond a basic outline and infuse a drawing with atmosphere, emotion, and life. This is the essence of graphite art, where the interplay of light and dark transforms a blank page into a living, breathing composition, an act of sculpting with light.

Shading is the profound language of a pencil, a lexicon of whispers and shouts. With the lightest touch, an artist can suggest the gentle whisper of sunlight on a surface, a fleeting highlight that speaks of softness and form. Conversely, a deeper, more forceful stroke can render the dense, dark depth of a shadow, giving an object its weight and grounding it in space. This tonal mastery is where the beauty of graphite truly shines, allowing for a spectrum of values from the brilliant white of the paper to the deepest, velvety black.

|

Leonardo da Vinci, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

Throughout history, renowned artists have used this method to capture the world. Masters like Edgar Degas employed pencil shading with poetic skill, layering tone with the same precision a composer uses to build a symphony, creating depth and a sense of movement in his studies of dancers.

Similarly, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was a virtuoso of graphite, crafting cool, classical portraits where every line and shadow resonated with grace and balance, defining form with a clean, almost architectural clarity.

Ultimately, the pencil allows an artist to simulate the full range of colors using only monochrome values. By varying pressure, layering lines, or carefully applying cross-hatching, an artist can bring stunning dimensionality to life.

In this way, a pencil drawing becomes a form of black, white, and gray painting, yet it is capable of evoking all the emotions that a full-color palette can stir.

A dark shadow can suggest melancholy or mystery, while a bright highlight can convey joy or hope. Leonardo da Vinci understood this concept implicitly. His anatomical sketches, rendered in pencil or silverpoint, were not merely studies; they were profound acts of reverence, with each meticulously shaded line imbued with an awe for the mechanics of life. His drawings demonstrate that a two-dimensional rendering can achieve a sense of visceral, three-dimensional reality through the careful use of tone.

Nowhere does the power of the pencil shine more beautifully than in animal studies. And among these, the horse stands supreme. A well-executed pencil drawing of a horse captures not only its anatomy but also its nobility, energy, and silent presence. A slight shift in shading around a horse’s eye can convey wariness or kindness, while purposeful strokes can evoke the rough texture of a mane or the silken smoothness of its coat.

The artist's empathy and keen observation are transferred directly to the paper, allowing us to feel the horse's weight, to sense its quiet strength, and to appreciate the intricate dance of light and shadow across its muscular form.

For those looking to master this craft, learning how to draw a horse with a pencil requires attention to form and technique. Begin with a light line to establish the contours of the body, allowing your hand to feel its way into the form without commitment. Once the foundational line work is in place, the true magic of shading begins. Decide on your light source and allow it to dictate where your shadows fall.

For instance, the soft curve of a flank might receive a gentle, blended shadow, while the deep recess under a lifted head requires a dense, dark tone. Use a soft pencil (such as a 4B or 6B) for the deepest shadows under the chin or behind an ear, and a harder pencil (H or HB) for the areas of highlight, like the bridge of the nose. Varying your technique—from cross-hatching for muscular areas to long, sweeping strokes for a flowing tail—adds vitality and realism. The goal is not to create a static image, but to capture the living, breathing energy of the subject.

The power of a pencil drawing also lies in its potential. Many artists use a pencil sketch as the underlayer for more elaborate works, such as watercolors or oil paintings. The pencil acts as a tonal map or a blueprint, guiding the final application of color. A painter can follow the graphite cues, applying warm hues where shadows deepen and cool tones where light grazes the surface.

This preparatory work allows the artist to focus on color and texture without losing the foundational form and tonal structure. Yet, some drawings, like the works of artist Jeanne Rewa, stand alone in their complete and beautiful simplicity. In their modest, monochrome form, they resonate with a quiet power that needs no further embellishment, proving that the pencil is not merely a tool of preparation, but a medium of finished art in itself.

In our digital age, where every image is vibrant and often filtered, the pencil remains an immediate, personal, and unfiltered tool. Its beauty lies in its humility and directness. A pencil drawing is as close as one can come to the mind's eye rendered visible, a direct transfer of observation and emotion from artist to paper. It captures not just what is seen, but what is felt—a quiet miracle that allows us to connect with the artist’s unique perspective and feel the life within the lines.

No comments:

Post a Comment