|

| Jerusalem ladder east side track Vasily Polenov, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

It’s rarely framed in a gallery, and it seldom makes it into glossy art books. Yet, this humble stage of the creative journey is where most of the thinking, problem-solving, and soul of a piece begins.

The preparatory drawing is the skeleton beneath the skin of art, the blueprint from which the final structure emerges. Without it, a finished piece may still be beautiful, but it risks lacking the coherence, balance, and clarity that give artwork its quiet authority.

1. What Exactly is a Preparatory Drawing?

A preparatory drawing is essentially the artist’s draft. It can be a loose sketch or a meticulously planned layout, created before the main work begins. The purpose is not to impress, but to plan: to work out proportions, explore composition, and experiment with shapes, light, and shadow. It might be done quickly, with faint lines and erased corrections, or it might take hours of careful observation and adjustment. Regardless of its formality, its goal is the same — to think visually before committing to the final portrayal.

In pencil work, a preparatory drawing allows the artist to understand how fine lines, hatching, and shading will interact. In color work — whether watercolor, colored pencil, gouache, or pastel — it’s where the artist decides how colors will relate, how contrast will guide the eye, and how the values (lightness and darkness) will underpin the hues.

2. The Role of Observation

|

| Vasily Polenov, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Christ and the woman taken in adultery |

But in doing so, we miss an essential phase: the deep observation that only comes when we take the time to map things out.

A preparatory drawing forces you to really see your subject — its subtle curves, the relationship between forms, and the way light falls.

For example, in portraiture, rushing to color without planning can result in features slightly misaligned, an expression that feels unintentionally different, or a composition that lacks breathing space. A preparatory drawing helps the artist to capture the proportions of a face, the tilt of a head, the rhythm of a gesture. This deep study pays off not only in accuracy but in emotional truth.

3. Composition: The Hidden Architecture

In any artwork, composition — the arrangement of elements in space — is what makes the difference between a pleasing, harmonious image and one that feels awkward or cramped. Preparatory drawings are where composition is born. The artist can try out different viewpoints, shift the balance between positive and negative space, and decide where the viewer’s eye should enter and exit the frame.

Sometimes an artist might make several small preparatory sketches, called thumbnails, just to test composition ideas. These might be no larger than a playing card, yet they can determine the success of a much larger piece. In both pencil and color work, planning composition in advance prevents later frustration and wasted effort.

4. Problem-Solving Before the Commitment

Working in pencil offers some flexibility for correction — lines can be erased, tones can be lightened. But in many color mediums, mistakes are harder to undo. Watercolor stains the paper; pastel layers can only be reworked so far; even colored pencil has limits before the paper’s surface loses its ability to hold pigment. A preparatory drawing acts as a safety net. By solving structural problems ahead of time, the artist enters the final stage with confidence, knowing the foundations are sound.

For example, in a still-life color portrayal, the preparatory drawing can establish the relationship between objects and the light source. Is that shadow too long? Will the apple overlap awkwardly with the vase? These questions are best answered before the final materials are touched.

5. Understanding Value Before Color

|

| shakko, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons Christ and the woman taken in adultery |

A preparatory drawing, especially one done in graphite or charcoal, allows the artist to work out the value structure before adding the distraction of color. This is particularly important because the brain can be tricked by hue; a bright color might seem lighter than it really is.

By focusing on value first, the artist ensures that the final work will have strong contrasts and a clear sense of volume.

Even seasoned colorists often make monochrome preparatory studies. They know that if the value relationships are correct, the final colors will almost automatically fall into place.

6. The Emotional Warm-Up

Beyond the technical benefits, a preparatory drawing also serves as a warm-up for the artist’s mind and hand. Drawing is a physical activity: the muscles of the fingers, wrist, and arm need to adjust to the subject’s scale and movement. The brain needs to shift into a mode of intense focus. A preparatory stage is like stretching before a run — it prepares the body and mind for the real exertion ahead.

In many cases, artists report that the preparatory drawing helps them connect emotionally with the subject. By spending time on preliminary lines, they begin to sense the personality of a figure, the quiet dignity of a building, or the mood of a landscape. This emotional connection often seeps into the final portrayal, making it more than just a technical reproduction.

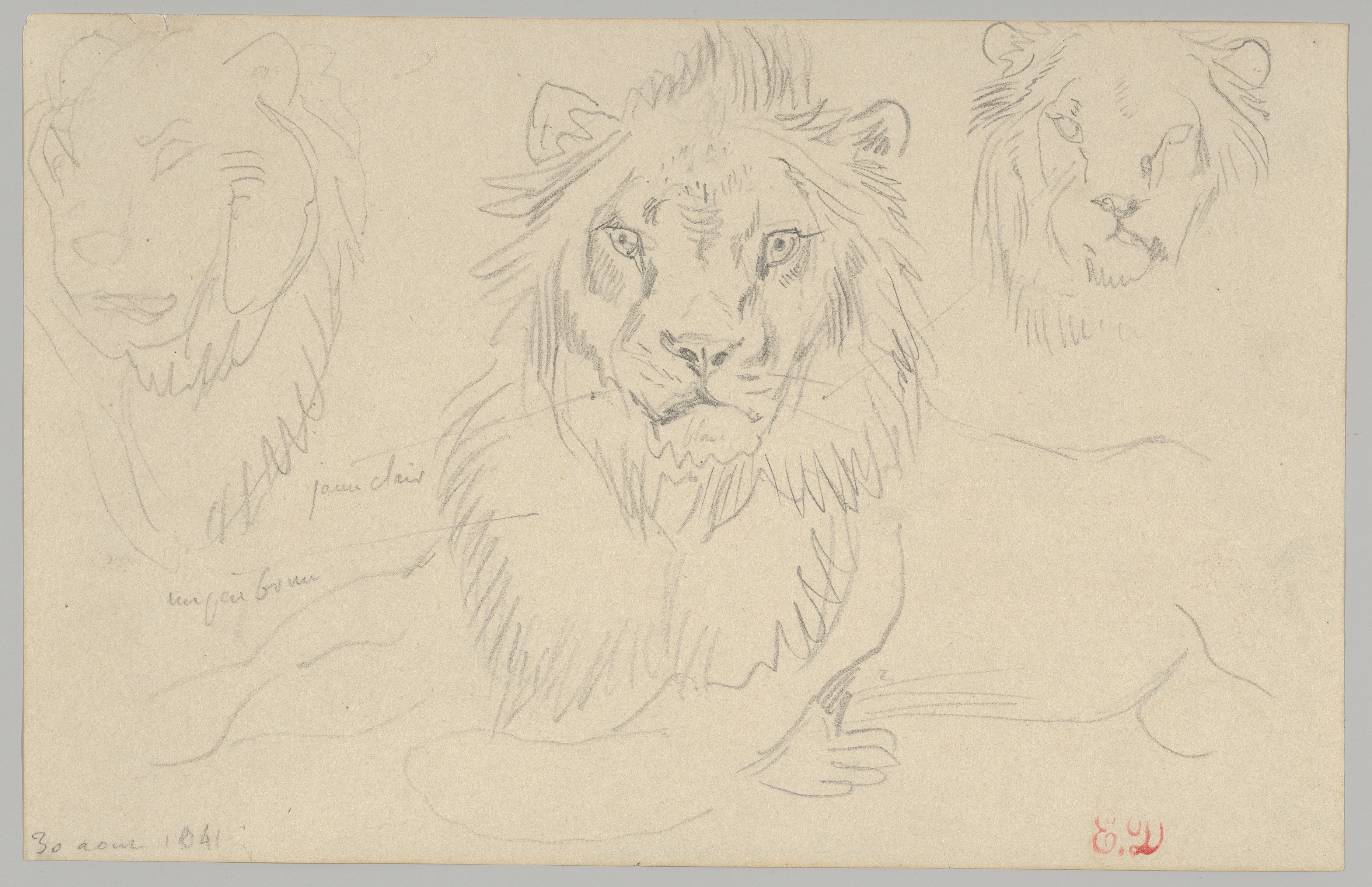

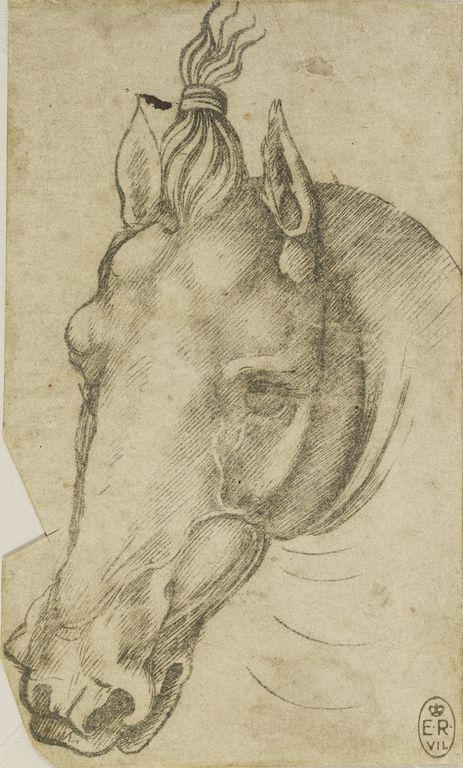

7. Historical Perspective

Looking back through art history, we see that preparatory drawings have always been vital. Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbooks are filled with studies for paintings and sculptures — hands, horses, draperies, faces — each a rehearsal for the final work. Michelangelo’s rough sketches for the Sistine Chapel ceiling show his thinking process, solving anatomical puzzles before committing paint to plaster. Even in the 19th and 20th centuries, artists like Degas and Picasso relied on countless preliminary studies to refine their compositions.

These preparatory works were not only tools but treasures in their own right. Today, museums exhibit them alongside the finished masterpieces, revealing the artist’s hidden labor and experimentation.

8. In Pencil Portrayal

When the final piece is intended to be in graphite or charcoal, the preparatory drawing might be almost indistinguishable from the final work — except that it’s looser, more exploratory. Pencil portrayal demands precision in edges, tones, and textures. A preparatory phase allows the artist to experiment with mark-making techniques: should the texture of a jacket be rendered in tight crosshatching, or with soft blended shading? Should the background remain stark white or be toned down to push the subject forward? By answering these questions early, the artist ensures that every mark in the final work is intentional.

9. In Color Portrayal

|

| shakko, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons Christ and the woman taken in adultery |

In color work, the preparatory drawing becomes even more crucial. Unlike pencil, where changes can be made easily, many color mediums are unforgiving. Artists often transfer their preparatory drawing directly onto the final paper or canvas to avoid re-measuring and redrawing.

This stage also offers the chance to create a color study — a small painted or penciled version of the work to test color combinations and layering techniques.

For example, in colored pencil art, a preparatory drawing might establish where the deepest shadows will be so that the artist can layer the darker pigments first. In watercolor, the drawing can indicate where the paper must remain untouched for highlights, as lifting paint later might be impossible.

10. Avoiding Over-Working

One subtle benefit of preparatory drawing is that it prevents over-working the final piece. Without a plan, an artist might fuss endlessly, adding and removing details in search of harmony. This often results in a surface that looks tired or muddy. A preparatory stage, by contrast, clarifies the path forward. The artist can execute the final portrayal with fresh marks and confident color choices, preserving the energy of the work.

11. The Artist’s Private Language

For many, the preparatory drawing is not meant for anyone else’s eyes. It can be messy, full of notes, arrows, and quick lines. It’s a space for private experimentation — a place where the artist can make “mistakes” without fear. This freedom encourages risk-taking and creativity. Ironically, some preparatory drawings, with their raw vitality, end up feeling more alive than the polished final work.

12. Teaching and Learning

In art education, preparatory drawing is a crucial teaching tool. It trains students to think ahead, to break down complex forms into basic shapes, and to see the underlying structure of a subject. Beginners often resist it, eager to jump to the “fun” part, but once they experience how much smoother the final process becomes, they start to value it.

Teachers often encourage students to keep all their preparatory work, even after finishing the main piece. Looking back, students can trace their own progress and see how their problem-solving skills have evolved.

13. Modern Adaptations

In the digital age, preparatory drawing hasn’t disappeared — it has simply adapted. Many artists now do their preliminary sketches on tablets, using layers to experiment with composition and color. The advantage here is the ease of editing: objects can be moved, resized, or recolored instantly. Yet, even in this high-tech form, the principle remains the same: the artist is thinking ahead before committing to the final work.

Interestingly, many digital artists still find value in doing a hand-drawn preparatory sketch before moving to the screen. The tactile act of drawing on paper engages different parts of the brain, encouraging a slower, more deliberate observation.

14. Conclusion: The Invisible Art

The preparatory drawing is a paradox — it’s the part of the artwork most viewers never see, yet it holds the key to the success of the final piece. It blends observation, composition, problem-solving, and emotional engagement into a quiet foundation. Whether the artist is working in monochrome pencil or a kaleidoscope of colors, the preparatory stage ensures that the final portrayal stands on solid ground.

Far from being a mere formality, it’s a space where the artist learns, experiments, and makes decisions without fear. It’s where ideas are born and tested. And though it may be erased, covered, or hidden beneath layers of pigment, the preparatory drawing remains — like the unseen roots of a tree — silently supporting all that blooms above.