Pencil Drawing: The Art of Simplicity, Precision, and Emotional Depth

|

| Portrait of Ellen Smith Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Pencil drawing is one of the most timeless and expressive forms of visual art. Unlike painting, which relies on vibrant colors and large canvases, graphite art communicates through subtlety—capturing depth, emotion, and detail with the stroke of a pencil.

This quiet medium offers immediacy and intimacy, inviting both artist and viewer into a reflective, nuanced experience.

What sets pencil drawing apart is its flexibility. Mistakes can be erased, lines reshaped, and ideas refined in real-time.

This spontaneity makes it an ideal medium for beginners and professionals alike, yet achieving true mastery demands discipline, control, and a deep understanding of light and shadow.

|

| Primary Figures of Pets Image generated with the assistance of ChatGPT (OpenAI) |

Whether creating quick studies or intricate pencil portraits, this medium excels at conveying raw emotion and fine detail. Its accessibility makes it popular, but its artistic depth keeps it revered.

This article delves into the core techniques of pencil drawing, the unique aesthetic of graphite, and showcases five celebrated pencil artworks and three iconic pencil portraits that highlight the poetic potential of the medium.

Ley us discover how pencil drawing transforms simplicity into sophistication—one line at a time.

The Medium: From Graphite to Greatness

Graphite, discovered in the 16th century in England, revolutionized the concept of drawing. Unlike charcoal, graphite offered greater control and permanence, while being softer than metalpoint or ink.

|

Turbojet, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Common |

Artists manipulate this range by adjusting pressure, layering strokes, or blending with stumps and fingers.

It allows for expressive gesture drawing, detailed realism, and everything in between.

Fundamentals of Pencil Drawing

To understand pencil drawing deeply, one must begin with its fundamental principles:

1. Line

Line is the skeleton of drawing. It defines contours, edges, and structure. In skilled hands, a line can be elegant or assertive, fluid or tense. A confident line reflects a confident artist. Hatching, cross-hatching, and contour lines are techniques that bring dynamism and rhythm to drawings.

2. Tone and Value

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Tone refers to the lightness or darkness of a mark. Value is the broader concept of light and dark relationships across the whole composition. Mastery of value is essential to create depth, volume, and atmosphere. Shadows, highlights, and mid-tones must harmonize to evoke realism.

3. Form and Perspective

Form gives volume to shapes. Understanding light direction, cast shadow, and reflective light helps in building three-dimensionality on paper. Perspective, whether linear or atmospheric, organizes space and distance, allowing artists to suggest depth convincingly.

4. Texture

Through texture, an artist conveys the surface quality of an object—be it rough stone, smooth skin, or wispy hair. Pencil excels at rendering texture due to its sensitivity to pressure and gesture.

5. Composition

A balanced composition guides the viewer’s eye and evokes emotional responses. Even in simple drawings, placement, spacing, and focal points play crucial roles.

Five Masterful Pencil Drawings

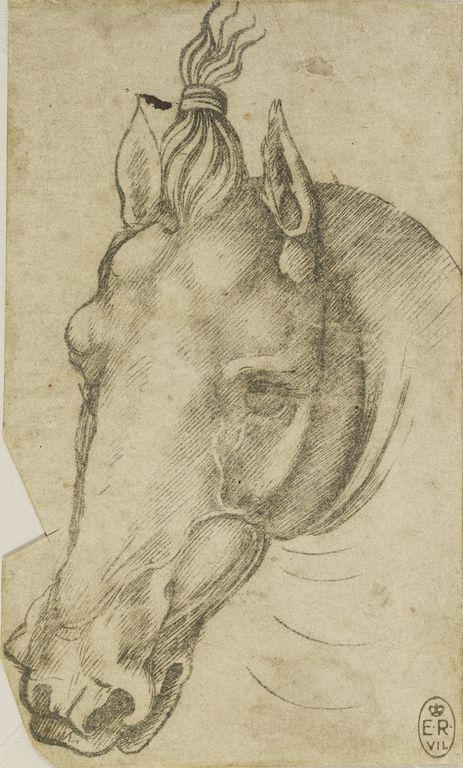

1. Leonardo da Vinci – Study of a Horse (c. 1490)

|

Leonardo da Vinci, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of a horse is a masterclass in using fine, delicate lines to carefully model the animal’s musculature and stance.

With remarkable skill, he captures a sense of motion and grace that makes the horse feel truly alive.

The soft gradation of graphite brings out subtle shadows along the flanks and joints, giving the form a three-dimensional quality.

Leonardo masterfully employs line variation—using thicker lines in darker areas and lighter ones where the light hits—to model the volume and weight of the animal.

This sketch is far more than a simple preparatory study; it stands as a complete and beautiful meditation on the power and elegance of the equine form, showcasing a deep understanding of anatomy and movement.

2. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres – Study for Madame Moitessier (c. 1850)

|

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

3. Albrecht Dürer – Praying Hands (c. 1508)

|

Albrecht Dürer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

4. Vincent van Gogh – Sower with Setting Sun (Drawing) (c. 1888)

Though Van Gogh is famous for his vibrant paintings, his pencil drawings, particularly of peasants and rural life, are rich in feeling. In Sower with Setting Sun, Van Gogh uses strong directional lines to suggest movement and intensity. The farmer’s figure is built from energetic, jagged strokes, while the setting sun behind him glows in contrast through a halo of softened shading. It’s not realism Van Gogh seeks but emotional resonance—and he achieves it through powerful mark-making.

5. Gustave Doré – Illustration for Dante’s Inferno (19th century)

Gustave Doré’s drawings, created for literary illustration, push the pencil to dramatic ends. In his Inferno drawings, swirling clouds, tortured souls, and vast infernal landscapes emerge from intricate layers of graphite. His mastery of chiaroscuro—extreme contrasts of light and dark—elevates his drawings into haunting, almost cinematic realms. The pencil becomes an instrument of dramatic storytelling.

Three Iconic Pencil Portraits by Master Artists

1. Leonardo da Vinci – Portrait of a Young Woman (La Scapigliata) (c. 1508)

|

| Head of AWoman Leonardo da Vinci, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

2. Hans Holbein the Younger – Portrait of Anne Cresacre (c. 1532)

|

| Anne Cresacre (c.1511-77) Hans Holbein the Younger, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Hans Holbein the Younger's drawing of Anne Cresacre is a poignant study for his now-destroyed group portrait of the family of Sir Thomas More. Anne Cresacre (1511–77) was the ward of More, who took her in after her father's death. She was betrothed to More's only son, John, in 1527, and the two married in 1529.

This drawing, one of seven surviving studies for the large portrait, offers a fascinating glimpse into Holbein's process. The back of a chair visible on the left suggests that Anne was originally intended to be seated in the final composition. However, a later sketch and written descriptions of the finished work confirm that she was ultimately depicted standing, with her husband, John More, nearby.

This drawing is not only a masterpiece of Holbein's meticulous hand but also a valuable historical record, providing a rare look at the intimate world of the More family and the artistic changes made during the creation of a monumental work.

In Anne Cresacre, Holbein captures the young woman’s serene gaze with elegant restraint.

The lines are confident, the shading precise yet subtle. Every feature—eyebrows, nostrils, lips—is carefully observed.

The drawing has a calm dignity and becomes a psychological study more than just a likeness.

3. John Singer Sargent – Portrait of a Young Man (c. 1890s)

Though known for his flamboyant oil portraits, Sargent’s pencil portraits are exercises in brevity and fluency. In this drawing, he uses swift, gestural strokes to define the jawline, the arch of the nose, and the curls of hair. Sargent’s pencil lines seem to dance—improvised yet always controlled. The portrait is energetic and intimate, revealing not just the appearance but the personality of the sitter.

Why Pencil Drawing Endures

Despite centuries of change in the art world—new materials, technologies, and conceptual frameworks—pencil drawing remains a cornerstone of visual expression. Why?

1. Accessibility and Universality

A pencil and paper are enough to begin. There is no hierarchy in tools—students and masters alike draw with graphite. This accessibility has democratized art, making drawing a universal language.

2. Intimacy and Immediacy

Unlike painting, which can be layered and mediated, drawing is immediate. It reflects the artist’s hand, mood, and hesitation. In many ways, it is the most honest medium—mistakes are visible, changes traceable. Every line has presence.

3. Foundation for All Visual Arts

Pencil drawing underlies virtually every other visual discipline. Painters sketch compositions; sculptors draw studies from life. Architects, animators, illustrators—most begin with a pencil. Mastery of drawing builds visual intelligence and observational skill.

4. Range of Expression

From tight academic realism to wild abstraction, pencil drawing accommodates all styles. Artists like Dürer and Ingres sought exactitude; Van Gogh and Egon Schiele pursued expression. The pencil is adaptable to intention.

Mastering the Craft: Practice and Patience

To become proficient in pencil drawing, artists must dedicate time to observation, repetition, and refinement. The process involves:

-

Life Drawing: Observing and drawing from live models sharpens perception and anatomy.

-

Still Life Studies: Learning to render volume, light, and spatial relationships.

-

Gesture Drawing: Quick sketches to capture movement and energy.

-

Portrait Drawing: Understanding the proportions and psychology of the human face.

-

Value Studies: Focusing on tonal range without depending on outlines.

It’s not only the technical mastery that matters—but also the development of an eye that sees—not just looks. Great drawing is 90% observation and 10% execution.

Conclusion

Pencil drawing is a dance between discipline and freedom, between form and feeling.

It is the point where art and thought touch the page at once. From Leonardo’s anatomical studies to Sargent’s lightning-quick portraits, from Holbein’s poised sitters to Van Gogh’s emotionally charged scenes—each artist reveals a truth unique to pencil.

In a world increasingly saturated with digital imagery, the analog presence of graphite on paper holds a special significance.

It is slow, meditative, and material. Every mark has weight. Every erasure tells a story. Pencil drawing may be humble in appearance, but in essence, it is profound, connecting mind, hand, and eye in the most direct form of visual poetry.

No comments:

Post a Comment