INTRODUCTION

|

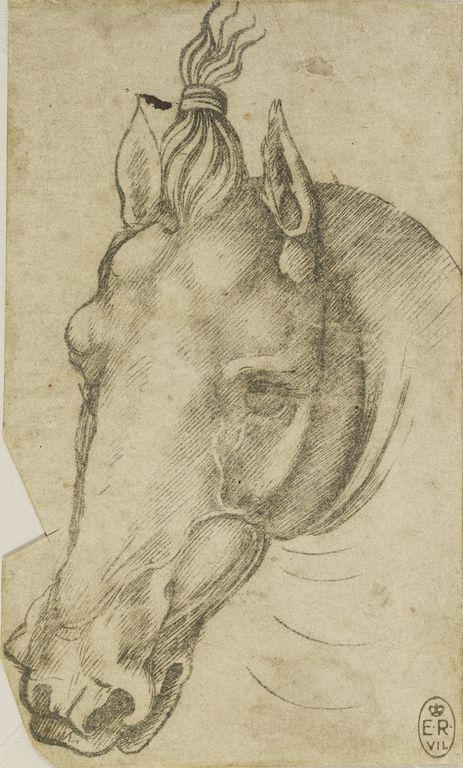

| Leonardo da Vinci, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}} |

In this essay, we’ll explore the magic of pencil shading, the history of great masters who used it, the techniques that bring horses to life on paper, and why the humble pencil continues to hold power in our digital age.

Why Pencil Shading Matters in Art

What makes the pencil so remarkable is not merely its ability to sketch outlines but its mastery of shadow and tonality. With subtle changes in pressure, an artist can suggest not just the outline of a horse but also the weight of its body, the softness of its coat, and the shimmer in its eyes. Shading transforms a drawing from a flat diagram into a living presence.

Pencil shading is like a language unto itself. A faint touch conveys the whisper of sunlight grazing a horse’s flank, while a darker, more deliberate stroke defines the deep muscle of the shoulder or the intensity of a shadowed gaze. This range of tonal expression gives pencil art its depth and resonance, turning monochrome marks into emotional experiences.

Masters of Pencil Shading: From Da Vinci to Degas

Throughout art history, the pencil has been the preferred tool of many great masters. Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, used pencil and silverpoint to sketch human anatomy with awe and reverence. His shading was not merely functional but an act of devotion to life’s complexity.

Edgar Degas also mastered pencil shading, layering graphite with the same sensitivity that a composer brings to harmony. His drawings pulse with rhythm, movement, and atmosphere. Similarly, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres demonstrated graphite’s potential in his portraits, balancing cool precision with expressive tonality.

These artists remind us that pencil drawing is not a lesser form of art but a foundation for visual expression. In many cases, pencil studies carry as much emotional weight as finished paintings.

Tonal Values: Painting with Graphite

When shading with a pencil, artists essentially “paint” with shades of grey. By pressing harder or layering cross-hatched lines, one can simulate the depth and richness of color without ever touching paint. In this sense, pencil drawing is a monochrome form of painting, capturing the same spectrum of emotion that color can evoke.

Graphite is uniquely suited for this task because of its fine modulation. It allows delicate whispers of shadow or bold, dramatic contrasts. This versatility explains why pencil has replaced older tools like chalk and charcoal for many artists: it offers control, intimacy, and subtlety unmatched by other mediums.

Why Horses Are a Favorite Subject for Pencil Artists

Among animal subjects, the horse stands supreme in pencil drawing. Horses embody a blend of anatomy, elegance, and symbolic power that challenges and rewards the artist’s skill. A single drawing can capture not only the physical presence of a horse but also its nobility, energy, and quiet dignity.

Take, for example, the horse’s eye. With just a shift in shading around the socket, an artist can suggest kindness, alertness, or melancholy. The ears, pricked toward a sound, require delicate, curved strokes, while the mane invites experimentation with texture through short, rhythmic lines. The horse’s musculature also provides endless opportunity for cross-hatching and blending to convey strength beneath the skin.

One stunning example is the work of Jeanne Rewa, whose pencil drawings of horses reveal sensitivity and mastery of shadow. Her rendering of two horses with their heads lowered directs not only their gaze but also the viewer’s, guiding our eyes downward with carefully layered shading. The result is a drawing that feels alive, narrating a moment in time rather than simply depicting anatomy.

How to Draw and Shade a Horse with Pencil

For aspiring artists, drawing horses in pencil is both a challenge and a joy. Below are key steps and techniques to consider:

1. Begin with Light Line Work

Start by sketching the basic contours—the arch of the neck, the curve of the muzzle, the angles of the legs. Use light pressure so the lines can be adjusted easily. At this stage, think of yourself as “tuning” the form, much like a musician preparing an instrument.

2. Establish the Light Source

Before shading, decide where your light is coming from. This determines where highlights and shadows fall. A consistent light source ensures your horse looks three-dimensional and believable.

3. Use Different Pencil Grades

Soft pencils (like 4B or 6B) are best for deep shadows, such as under the jaw or beneath the body. Harder pencils (like H or HB) create lighter values for areas where light strikes directly—the bridge of the nose, the forehead, or the back.

4. Vary Your Pressure

The beauty of graphite lies in pressure sensitivity. A gentle touch leaves a soft whisper of tone, while firm pressure creates rich, dark shadows. Experiment with layering to achieve smooth gradients.

5. Explore Techniques

-

Cross-hatching: Ideal for muscular areas like the chest or haunches.

-

Long sweeping strokes: Perfect for the mane and tail.

-

Blending: Use a blending stump or finger sparingly to soften shadows without losing texture.

Remember, a horse is not a statue. Leave some areas less finished to preserve vitality and motion.

Pencil Shading as a Foundation for Other Media

Many artists use pencil sketches as underdrawings for paintings or digital art. In these cases, shading acts as a tonal map, guiding where warm colors deepen or cool highlights emerge. This makes pencil not only a finished medium but also an indispensable step in larger works.

However, pencil drawings often stand alone. Works like Rewa’s horse portraits need no embellishment. Their monochrome modesty is part of their power, inviting viewers to appreciate form, shadow, and texture without distraction.

The Emotional Power of Pencil Drawing

The true miracle of pencil shading is its ability to transmit emotion. When we look at a well-drawn horse, we don’t just see anatomy—we feel presence. Through subtle variations of line and shadow, the artist conveys empathy, strength, and even memory.

At its best, pencil art allows us to enter the subject’s world. We feel the weight of the horse, the warmth of its body, the calm in its eye. We hear the faint echo of hoofbeats and smell the dust of the trail. This is not merely representation; it is interpretation, and it speaks directly to our imagination.

The Pencil in the Digital Age

In our world of high-resolution digital imagery, the pencil may seem modest, even outdated. Yet its enduring relevance lies in its immediacy and intimacy. A pencil drawing requires no software, no power source, no filters. It is a direct extension of thought to paper—a pure form of expression.

Artists continue to embrace pencil shading not because it is old-fashioned, but because it is timeless. Its simplicity hides a profound strength: the ability to capture the essence of life with nothing more than graphite and paper.

Conclusion: Drawing the Spirit of the Horse

To take up a pencil is to participate in a tradition that stretches back centuries. Each line is both personal and universal, connecting us to artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Degas, Ingres, and Jeanne Rewa. When we shade a horse, we are not just recording its form—we are honoring its spirit.

So set your paper before you. Let your lines be light at first, then deepen into shadows. Feel the rhythm of strokes as you render the mane, the weight of pressure as you carve out muscle and bone. Allow yourself to capture not just the horse’s appearance but also its freedom, memory, and power.

In the end, a pencil drawing of a horse is more than art—it is an act of empathy, a bridge between creator and creature. And with each stroke, the horse runs again, not across fields, but across the page, carrying its timeless spirit into our imagination.

No comments:

Post a Comment